|

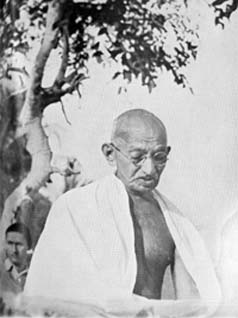

And then Gandhi came, He did not descend from

the top: he seemed to emerge from the millions of India, speaking their

language and incessantly drawing attention to them and their appalling

condition. Get off the backs of these peasants and workers, he told us, all

you who live by their exploitation; get rid of the system that produces this

poverty and misery. Political freedom took new shape then and that produces

this poverty and misery. Political freedom took new shape then and acquired

a new content. Much that he said we only partially accepted or some times

did not accept at all. But all this was secondary. The essence of his

teaching was fearlessness and truth and action allied to 6these, always

keeping the welfare of the masses in view. The greatest gift for an

individual or a nation, so we had been told in our ancient books, was abhaya,

fearlessness, not merely bodily courage but the absence of fear from the

mind. Janaka and Yajnavalkya had said, at the dawn of our history, that it

was the function of the leaders of a people to make them fearless. But the

dominant impulse in India under British rule was that of fear, pervasive,

oppressing, strangling fear; fear of the army, the police, the wide-spread

secret service; fear of the official class; fear of the laws meant to

suppress and of prison; fear of the landlord's agent; fear of the money

lender; fear of unemployment and starvation, which were always on the

threshold. It was against this all-pervading fear that Gandhi's quite and

determined voice was raised; be not afraid. Was it so simple as all that?

Not quite. And yet fear builds its phantoms which are more fearsome than

reality itself, and reality, when calmly analysed and its consequences

willingly accepted, loses much of its terror. And then Gandhi came, He did not descend from

the top: he seemed to emerge from the millions of India, speaking their

language and incessantly drawing attention to them and their appalling

condition. Get off the backs of these peasants and workers, he told us, all

you who live by their exploitation; get rid of the system that produces this

poverty and misery. Political freedom took new shape then and that produces

this poverty and misery. Political freedom took new shape then and acquired

a new content. Much that he said we only partially accepted or some times

did not accept at all. But all this was secondary. The essence of his

teaching was fearlessness and truth and action allied to 6these, always

keeping the welfare of the masses in view. The greatest gift for an

individual or a nation, so we had been told in our ancient books, was abhaya,

fearlessness, not merely bodily courage but the absence of fear from the

mind. Janaka and Yajnavalkya had said, at the dawn of our history, that it

was the function of the leaders of a people to make them fearless. But the

dominant impulse in India under British rule was that of fear, pervasive,

oppressing, strangling fear; fear of the army, the police, the wide-spread

secret service; fear of the official class; fear of the laws meant to

suppress and of prison; fear of the landlord's agent; fear of the money

lender; fear of unemployment and starvation, which were always on the

threshold. It was against this all-pervading fear that Gandhi's quite and

determined voice was raised; be not afraid. Was it so simple as all that?

Not quite. And yet fear builds its phantoms which are more fearsome than

reality itself, and reality, when calmly analysed and its consequences

willingly accepted, loses much of its terror.

So, suddenly as at were, that black pall of

fear was lifted from the people's shoulders, not wholly of course, but to an

amazing degree.

Jawaharlal Nehru

(The Discovery of India) |